A Brief History of Behavioural Economics and Its Contributions to Society

Behavioral economics is a relatively new field of study that has gained increasing attention in recent years. It explores how individuals make decisions in real-world settings, and how their behavior differs from what traditional economic theory predicts. Behavioral economics has been recognized in policy circles, with governments around the world adopting behavioral insights to improve policy outcomes. The UK government, for example, established the Behavioral Insights Team, or “Nudge Unit”, in 2010 to apply insights from behavioral economics to public policy. In this post, we explore the early days of behavioral economics and its major contributions to society.

The origins of behavioral economics can be traced back to the mid-20th century when psychologists and economists began to question the assumptions of traditional economic theory which at its core posited that human beings always acted rationally and in line with their interests. In the 1950s and 1960s, researchers such as Herbert Simon, Daniel Kahneman, and Amos Tversky began to challenge the notion of economic rationality.

One of the key events was the publication of Kahneman and Tversky’s seminal paper, “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk” in 1979. This paper introduced the concept of loss aversion, which refers to the tendency for individuals to weigh potential losses more heavily than potential gains. This theory might explain why, for example, people hang on to losing stocks for too long and sell winning stocks too early (Barber & Odean, 2000). Indeed, any person who loses money knows the pain of losing it is sharper than the joy of earning an equal amount. The paper also introduced the concept of framing, which refers to the way in which information is presented and how this can influence decision-making. Classical economists would argue that all else being equal, differences in how a product is framed should have no bearing on consumers’ preferences but the research suggests otherwise.

In the 1980s and 1990s, researchers like Richard Thaler began studying how individuals make decisions within the context of social norms and cognitive biases. In 2009, Thaler and Cass Sunstein published “Nudge,” introducing the concept of choice architecture and its role in influencing behavior. A nudge refers to a subtle modification in the environment that changes the status-quo or makes it easier for people to choose certain options. For example, automatically enrolling employees in a retirement savings plan has significantly increased participation rates (Thaler & Benartzi, 2004). People, whether consciously or subconsciously, tend to prefer the status quo because it is familiar and making changes requires effort. It’s a well-known fact that many of us can be lazy and voluntarily enrolling in a plan involves completing paperwork or checking a box requires action. Therefore, if the default option is changed to assume that people are willing participants, more individuals will by default become savers. Some may see nudging as paternalistic, but it is difficult to argue against saving money, as it benefits individuals and the economy.

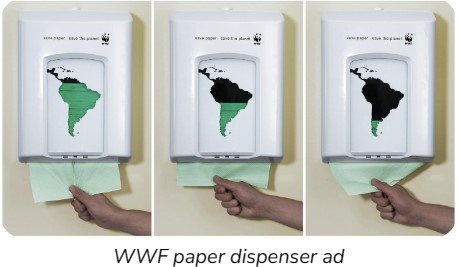

Climate change and sustainability are other areas where behavioral economics has made significant contributions. The field has helped researchers and policymakers design interventions that encourage people to adopt more sustainable behaviors. For example, studies have shown that providing people with feedback on their energy use can significantly reduce energy consumption (Darby, 2001). Similarly, making recycling bins more visible and accessible can encourage people to recycle more (Schultz, Oskamp, Mainieri, 1995). Behavioral economics has also been used to design policies such as carbon pricing. Carbon pricing places a tax on carbon emissions or requires companies to purchase permits to emit carbon. People are more likely to support such policies if they are framed as “green nudges” that encourage environmentally friendly behavior, rather than punitive measures (Tannenbaum et al., 2017).

Finally, behavioral economics has played a crucial role in improving risk communication between climate scientists and policymakers. For instance, research has shown that laypeople make better climate-related decisions and have more positive opinions about climate scientists when climate forecasts, such as temperature increases, include numerical uncertainty estimates (e.g., 90% chance that temperature increase will be between 1 and 3 degrees celsius) instead of deterministic forecasts (e.g., yearly temperature increase by 2 degrees celsisus; Joslyn & Demnitz, 2019; Demnitz & Joslyn, 2020). Although deterministic forecasts might create a stronger impression (e.g., “These scientists really know their stuff with such precision!”), it is the inclusion of uncertainty estimates that produces the best outcomes. Notably, these results were particularly pronounced among Americans who identify themselves as Republicans, a political group that often holds skepticism towards climate change.

While traditional economists have focused on how people should behave, behavioral economists have shed light on how people actually behave. Behavioral economists have shown that we are subject to biases and make decisions that are not always in our best interest, and these errors can sometimes be costly. However, by gaining a better understanding of how people function in the real world and the types of mistakes they make, we can design interventions that are effective. Rather than imposing heavy-handed and sometimes expensive interventions, behavioral economics advocates for laissez-faire interventions that work in harmony with human nature, rather than against it.