How many butterfly species exist? Are there more or less than 50? Well, if you’re not a butterfly expert, your answer probably didn’t stray too far from 50. This is because the number I provided influenced your estimate — a phenomenon known as the “anchoring effect”. While an anchor ideally shouldn’t affect your response, our minds can be subtly swayed by such information when other relevant cues are lacking.

Cogo, a startup, has developed a carbon footprint calculator using open banking to estimate the environmental impact of people’s spending. If you allow the app to access your transactions, it can calculate your carbon footprint. Cogo aimed to determine if people could be anchored to set a lower carbon footprint than their current one. Specifically, would individuals commit to a lower carbon footprint, and if so, by how much?

Another approach involves using social reference groups. Our tendency to conform to what similar people are doing is a powerful motivator. Opower, a provider of customer engagement solutions for utility companies, allows customers to compare their energy usage with similar homes. In a 2010 study, their program reduced energy consumption by 2.0%, saving over 32 terawatt hours of energy and $3.3 billion.1

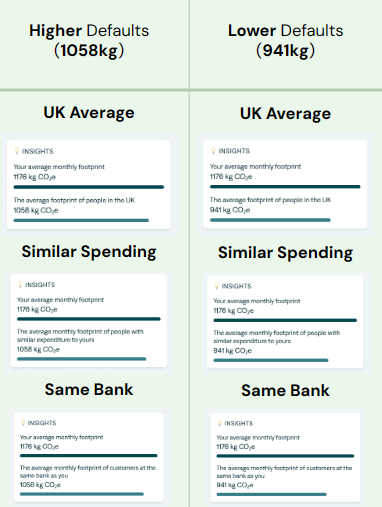

Similarly, could Cogo nudge users to commit to a lower carbon footprint by comparing theirs with similar individuals? To explore this, we invited over 2,000 people to participate in an online study, randomly assigning them to one of the conditions shown in the figure below.

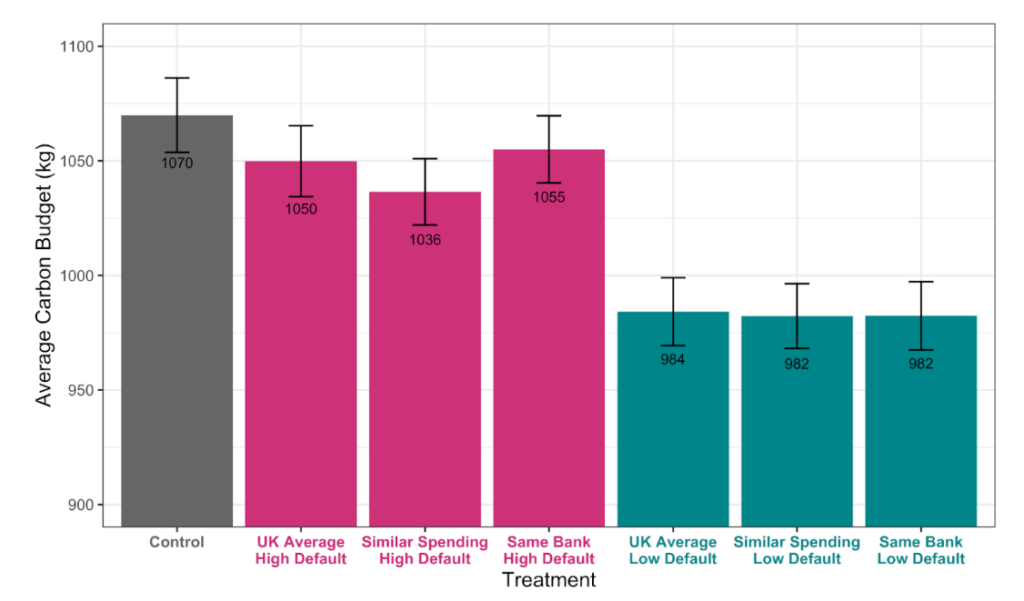

Our initial discovery revealed that providing individuals with information about the average carbon footprint of others was notably more effective than providing no information at all. Specifically, participants in all treatment conditions, on average, established lower carbon budgets for themselves (1,015kg) compared to those in the control condition (1,070kg) (p < .01).

Our second finding indicated that the identity of the social reference group did not significantly impact the outcomes. There was no substantial difference in the budgets set by individuals informed that the average footprint belonged to people in the UK, those with similar spending habits, or customers at the same bank.

Contrastingly, we observed that our anchoring values played a significant role, even more so than our social reference groups. As illustrated in the graph below, participants informed that the average carbon footprint of others was 941kg (as opposed to 1,058kg) set significantly lower carbon budgets (p < .0001).

These findings indicate that offering information about carbon footprints, whether related to others or provided as a default, is more effective than providing no information at all. This observation aligns with the expectation that people, in the absence of relevant cues, tend to utilize whatever information is available.

Crucially, the results emphasize that individuals are influenced by anchors in this context. Importantly, the decision to adopt the provided anchor should be left to the users themselves. Although social reference groups here had no effect, tinkering and experimenting with it in different ways should yield to an effect.